'The Imbecility of Our Union'

From Speaker McCarthy's Vacant Stare to Republicans' Simian Howls Over a Non-Existent 'Debt Ceiling,' We've Become Unrecognizable to any 'Us, the People.'

Anyone who spends even a few minutes reading the Federalist or Hamilton’s Treasury Reports will be struck by our first Treasury Secretary’s frequent use of the word ‘imbecile’ and its cognate, ‘imbecility.’ If you read with a 21st century sensibility, you might think he means something like idiocy or stupidity - the sort of thing manifest daily in apelike hooting by the likes of a Marjorie Taylor Greene or Lauren Boebert, or in the curiously vacuous stares of a Kevin McCarthy or Matt Gaetz, all of these creatures now peopling a shockingly debased U.S. Congress.

In fact, however, Hamilton meant something distinct, if related. He meant the want of composure, of composition, in any locus of agency needful of being composed or coherent to exercise agency. An ‘imbecile union,’ in Hamilton’s rendering, was effectively the outer form of a union without the inner ligature of a union. A ‘union’ without unity, a pluribus without unum - in short, a pathos-wrought contradiction in terms.

The conceptual tie between this form of imbecility and that of a Trump, Gaetz or Greene is clear enough - we say of the Propecia-poisoned or the insane, after all, that they are not compos mentis, not ‘of composed mind.’ But the mind Hamilton meant was the ‘common mind’ ordered by a common cause or purpose pursued by a polity acting in unison - a mode of collective agency exercised by individual agents in pursuit of collective ends, shared goals. A res publica, a republic or ‘thing of the public’ considered as One made of Many - e pluribus unum.

Against this backdrop, the current Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives - the aforementioned Kevin McCarthy - is in for an unpleasant reaction today when he comes to New York, hat in hand, hoping to enlist Wall Street’s support for his and his imbecile Party’s plan to disintegrate the American Union not only socially, as they have been doing for decades now, but also fiscally and financially, as they have attempted repeatedly since 2011.

Wall Street will first spot the weak composition of the Speaker’s own mind as manifest in his strangely blank stare, then puzzle over the mere quasi-composition of the Speaker’s five caucus-fragments (fittingly called now ‘the five families’) as manifest in his tenuous grip on the Speakership, then finally shudder over the outright fiscal-cum-financial decomposition of the American Union he will effectively be seeking their support for.

The immediate sign of the horror he brings will be market turbulence as traders confront what the loss of the world’s premier financial market (the over $25 trillion Treasurys market), not to mention the sole ‘risk-free asset’ that all Wall Street pricing models presuppose, would mean for the U.S. and global economies. The longer term sign will be global melt-down, deflation, and war - the stuff of the 1930s, save this time with nuclear weapons.

In hopes of preempting McCarthy’s and other Republican’s long-sought doomsday, however, I’d like to offer a comforting observation - viz., that there is no real ‘debt ceiling’ apart from the federal budget itself. The President, the Congress, and Wall Street along with the wider world can ignore Mr. McCarthy, ignore his non-caucusing pseudo-caucus, and ignore their faux debt ceiling as just one more TikTok or Instagram cat video. For again, the federal budget, is its own debt ceiling.

Here’s what I mean …

American lawyers whose tort classes used one or another edition of the old William Prosser casebook will recall an archaic Kansas statute, apparently apocryphal, that Professor Prosser noted for tongue-in-cheek pedagogical purposes. This statute was said to have required, of the conductors of any two trains that approached one another from opposite directions, that each was to halt his or her train and wait for the other to pass.

The pedagogical point here, of course, had to do with what we’re to do in response to a statute that cannot actually have been meant to prescribe or proscribe what it seems to prescribe or proscribe – since presumably no legislature would ever seriously intend, for example, that the railways be clogged by immobile trains all putatively waiting for one another to pass.

As it happens, lawyers and courts over literal centuries have developed widely-used means of dealing with conundrums like that raised by the proverbial Kansas statute. Conundrums do regularly arise, after all, even if not always as comically as in the train story.

Massive bodies of law like any U.S. State’s statute book or the U.S. Code grow organically over time, such that later-enacted legislation can easily come into conflict with earlier-enacted legislation, sometimes in ways that escape notice by newly legislating legislators who haven’t memorized decades’ or centuries’ worth of past legislation. When that happens, neither our States nor our Republic can afford simply to cease all action – like those two Kansas trains! – while waiting for new legislators to go back and harmonize all new enactments with all prior laws.

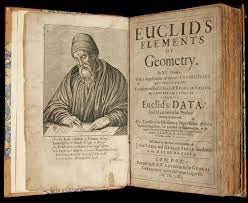

Law codes aren’t Euclid’s Elements or Newton’s Principia, after all. They aren’t formal systems whose axioms aspire to full theoretic completeness and internal consistency once and for all. They are practical instruments we use to address public challenges and coordinate interacting private activities publicly, and hence regularly expand and amend to respond to new circumstances.

Sometimes we do the latter via new legislation, and sometimes instead we use what the lawyers call ‘canons of interpretation.’ It is through these latter that we handle ambiguous or conflicted statutes like the proverbial Kansan one between sessions of legislative address.

At least three and in fact probably four such canons, I think, offer straightforward legal means by which President Biden and Treasury Secretary Yellen can simply ignore a stunt that’s now brewing in Congress. I refer to the latest Republican attempt at terrorist bargaining over a putative U.S. ‘debt ceiling.’

Biden and Yellen, I claim, can simply ignore the would-be hostage-taker this time, leaving the ball in their ‘court’ to hail Treasury into our Courts and then watch the Supreme Court annul it. Unless President Biden actually wants House Republicans to pretend to ‘take us to the brink,’ then – letting them thereby commit political suicide as their predecessors did back in 1995, 2011, and 2013 – he should simply announce that the ‘debt ceiling’ just ‘isn’t a thing’ and instruct Janet Yellen to disregard it.

What are these canons that I claim President Biden can cite? They are actually quite simple and, again, altogether familiar to lawyers both inside and outside the White House and Congress.

The first is what’s called the ‘later in time’ rule of statutory construction. The idea here, common-sensibly enough, is that where two legislative enactments appear to conflict, the later enactment will be read as implicitly repealing the earlier one – at least as applied in any manner that yields conflict. The applicability of this canon to the latest ‘debt ceiling’ imbroglio is straight-forward…

Since enactment of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, Congress has had ultimate control over the federal budget process, treating as merely advisory the President’s proposed budget each year. The ‘debt ceiling’ regime, by contrast, stems from the old Liberty Bond Act of 1917, passed by Congress as a means both of (a) conferring more budgetary discretion on the President in funding the U.S.’s First World War Effort, while also (b) imposing some minimal degree of control over the President’s use of that discretion during and immediately after the War.

That the ‘debt ceiling’ regime was never intended to apply to present circumstances, especially after 1974, of course is revealed by the fact that it wasn’t fought over by White Houses and Congress during the decades following 1917 … until opportunistic politicians beginning with Newt Gingrich in 1995 rediscovered it in the U.S. Code and decided to try their hands at employing it for stunt-performing purposes like shutting down the government.

Be that as it may, the important point right now is that both (a) the 1974 budget regime trumps the 1917 budget regime, and (b) the current budget trumps any putative ‘debt ceiling’ imposed after that budget became law.

The President should therefore just say that the last putative ceiling was implicitly repealed by the current budget, then note while at it that this also accords with Section 4 of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, more on which below, ratified by the former Confederate States as a condition on readmission to the Union. That provision prohibits questioning of the U.S. national debt, which compliance with any putative ‘debt ceiling’ imposed after debts are already incurred would amount to.

How about those other canons of statutory interpretation to which I alluded? Well these, as it happens, nicely complement the first. Start with the ‘absurd result’ canon. Pursuant to this one, a law that on one interpretation yields a result that cannot possibly have been rationally intended, while on another interpretation yields a result that could indeed rationally have been intended, must be read in keeping with the latter, rationally intendable interpretation. If, instead, there is literally no possible rational interpretation, the putative ‘law’ in question is treated as a nullity.

The absurd result canon of course offered means of dealing with the apocryphal Kansas train statute with which I opened. But it also carries over straightforwardly to the debt ceiling non-issue, in a manner that complements the later-in-time rule. For it is simply impossible to view Congress as having required both that the federal government issue Treasury securities pursuant to the latest budget, and not to borrow as much as required by that budget owing to earlier, putatively ‘limiting’ legislation.

We cannot, in other words, rationally interpret Congress as having done with fiscal legislation what the apocryphal Kansas legislature was said to have done with the aforementioned railway legislation. We must, then, instead view the most recent budget as having implicitly repealed any prior ‘debt ceiling’ legislation that would render compliance with the budget impossible.

A third canon-like norm of statutory construction in effect treats Constitutional conflict itself as a form of ‘absurd result’ to be averted when interpretively possible. I refer to the ‘Constitutional avoidance’ doctrine, pursuant to which a plausible statutory interpretation that avoids raising a Constitutional problem is to be preferred to one that does not avoid such a conflict. In the case of the ‘debt ceiling,’ the potential Constitutional conflict includes the one I alluded to earlier, along with several more.

First, then, Section 4 of the Constitution’s 14thAmendment prohibits impugning the national debt of the U.S. – something that Treasury Secretaries since our very first, Alexander Hamilton, have understood to be crucial to the integrity, stability, and indeed long-term survival of our republic. Under the most historically plausible interpretation of this clause, even for a federal official to suggest that our debts won’t be paid is a violation, ‘calling into question’ as it does the integrity of U.S. obligations.

But (ironically named) ‘Republican’ gamesmanship with the old Liberty Bond regime of 1917, pursued with a view to undermining confidence in the solvency of those U.S. sovereign debt instruments that are the bedrock of both the U.S. and the world financial systems, amounts to as dramatic a direct assault on the full faith and credit of the U.S. as can be imagined.

The Republican abuse of the debt ceiling also raises Constitutional issues under the Constitution’s ‘Take Care’ Clause found in Article II, Section 3, pursuant to which the President is required to ‘take care that the Laws [- including the federal budget -] be faithfully executed,’ and the Separation of Powers doctrine, pursuant to which Congress, not the President, determines under Article I how funds shall be spent and how taxes shall be raised.

Republicans’ apparent interpretation of the debt ceiling of course (a) would obstruct the President’s execution of the law in the ways mandated by the budget - which, again, is duly enacted Congressional legislation - and (b) confer on the Treasury, via the ‘extraordinary measures’ that it would have to take, a de facto line item veto of the kind the Supreme Court has ruled violates Article I and the Separation of Powers.

Any interpretation of the debt ceiling regime that looks to threaten default, violate the Take Care Clause, or offend Article I and the Separation of Powers, then, must be rejected under the constitutional avoidance canon in view of its raising a Constitutional conflict. It must instead be interpreted as the later-in-time rule and the absurd result canon discussed above suggest.

A final canon of statutory construction that President Biden and Secretary Yellen might find helpful under present circumstances is known as the ‘specific trumps the general’ rule. Here the idea is that if a general prescription or proscription made by a legislature appears to conflict with a more specific proscription or prescription made by the legislature, the more general provision is to be read as implicitly including an exception for the specific provision. (A ‘no sidewalk littering’ ordinance, for example, will be read as compatible with another ordinance requiring that people salt their sidewalks when they are icy.)

Here again the canon in question enjoys straightforward application to present circumstances. Anybody who’s read or tried to read an annual federal budget know there are literally thousands of quite specific spending, taxing, and borrowing mandates laid out by Congress and signed into law by the President.

The so-called ‘debt ceiling,’ by contrast, says nothing directly about any of these thousands of budget line-items. Instead it speaks quite as generally as can be imagined, referring solely to an aggregate Treasury issuance amount starting with 1917’s First World War Liberty Bond issuance. The last-enacted budget – which, again, is the law – must accordingly be viewed as implicitly repealing any ‘ceiling’ legislation interpreted as conflicting with it.

Where does this leave us? I think it’s pretty straight-forward…

If President Biden, like Presidents Clinton and Obama before him, wishes to give would-be financial hostage-takers in Congress more rope to hang themselves with, he can of course play up the present pseudo-conflict, say that he ‘will not negotiate with terrorists’ or ‘cut Social Security or national defense,’ thank them for the de facto line item veto they’ve unconstitutionally conferred on him in the form of Secretary Yellen’s ‘extraordinary measures,’ and enjoy yet another public backlash against Republican House clown-shows.

If, on the other hand, the President decides that it is long since time to pull the plug on this farce so the nation can address real problems, he should simply inform Congressional Republicans that there is no debt ceiling apart from the budget that they themselves have enacted, then watch them either drop their latest hijack attempt or sue him and be told the same thing by the courts.

You state that "the ‘debt ceiling’ regime ... wasn’t fought over by White Houses and Congress during the decades following 1917 … until opportunistic politicians beginning with Newt Gingrich in 1995 rediscovered it in the U.S. Code and decided to try their hands at employing it for stunt-performing purposes like shutting down the government."

How then would you characterize what has been called "The First Debt Ceiling Crisis" (https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr783.pdf) which took place during the 83rd Congress, 1953-54, when the White House and both houses of Congress were controlled by Republicans? Was that not a "fight over the debt ceiling"?

I am so loving these bits of Hamilton’s history, the translations of the terms used in his day as compared to our understanding of these terms today, and the pared down explanations of the workings of the US Code. Honestly, the US Code is not something I have ever thought about (except in a, “There’s gotta be a law for this, right?” kind of way). Seems like it’s time to codify some pretty important non-positive law titles.